The complete guide to safe type narrowing in TypeScript

Say I'm building a TODO app with two tabs: done and pending tasks. To make the app routable, I put the active tab into the ?tab query parameter, so that mytodo.io?tab=done takes me directly to the done tasks. I implement routing like this (pardon my hand-coded querystring parser):

const tasks = {

done: [],

pending: [],

};

const tab = location.search

.split('&')

.map(f => f.split('='))

.find(p => p[0] === 'tab')?.[1];

const items = tasks[tab];And stupid TS complains: type X can't be used to index type { done: ...; pending: ...; }. I put the active tab into the URL myself, what do you want from me? Time to meet my little friend, tasks[tab as keyof typeof tasks].

But wait, TS has a point. No matter what you expect the URL to be, the user might manually put anything into the ?tab parameter, or remove it altogether, purposefully or by accident. The TS-detected type string | undefined is 100% correct, and bypassing TS checks with as opens my app to a variety of bugs caused by missing items.

Since the bug happens in the "real world" of JS, as opposed to the "type-only world" of TS, we need some real-life checks to make the code safe:

const items = (tab === 'done' || tab === 'pending')

? tasks[tab]

: tasks.pending;From TS point of view our condition is a "type narrowing" expression: in general, tab is of type string | undefined, but the condition only evaluates to true for tab of type 'done' | 'pending', and that can be safely used to index tasks object.

Type narrowing is useful when your program gets values from the outer world: reading localStorage, (or, in general, JSON-parsing strings), parsing URLs, or reading raw user input. You can also accept wider types as an API design choice to let users call mount('#mount') in addition to mount(document.querySelector('#mount')).

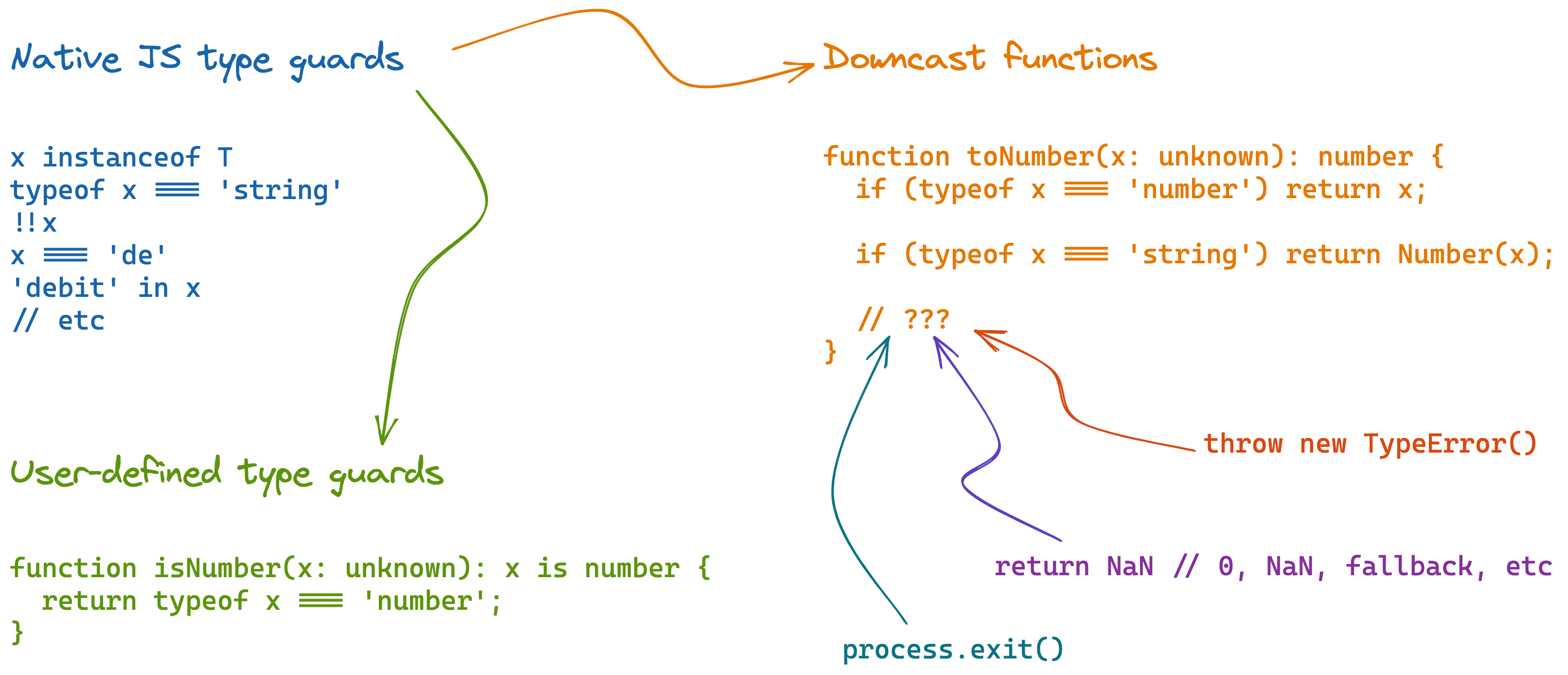

In this article, we cover several techniques to safely narrow variable types in TS:

- Using native JS operators, such as

typeof,===and more. - Detecting types inside custom functions, known as type guards. These are useful, but, surprisingly, not typesafe.

- Writing "downcast functions" that accept a wide-typed argument, but only return a narrow type, as in

(x: unknown) => number. We discuss four ways to make that happen.

Let's get started!

Type guards and control-flow analysis

JS has many tools to check the runtime type of a variable. TS is smart enough to see that some areas of code are only reachable for certain values of the variable, and narrow types there accordingly — this is known as control-flow analysis, or CFA. Here's a non-exhaustive list of things that natively narrow types in a JS / TS program:

function fun(x: string | number | Date) {

// typeof is an old favorite

if (typeof x === 'number') {

const res: number = x;

}

// equality operator is useful for casting to union / literal types

if (x === 'de') {

const country: 'de' = x;

}

// Date object can't be falsy

if (!x) {

const res: string | number = x;

}

// instanceof, typeof's object-oriented brother

if (x instanceof Object) {

const day = x.getDay();

}

// finally, 'in' can be used as a duck-type detector:

if (typeof x === 'object' && ('getDate' in x)) {

const day = x.getDay();

}

}Some narrowing operators (typeof, instanceof) actually access variable types, while the in operator implements a duck-typing check — we assume the type of a variable by looking at its property (if it has a peak, it's a duck). Similarly, we can narrow types of tagged unions based on the tag. For example, Transaction type contains amount in either debit or credit field, but we can alway tell wich one it is by lookig at direction:

type Transaction =

{ direction: 'incoming', debit: number } |

{ direction: 'outgoing', credit: number };

function amount(t: Transaction) {

return t.direction === 'incoming' ? t.debit : t.credit;

}This function can also be implemented using an in operator, because the mere presence of debit / credit field tells us which kind of transaction we're looking at: 'debit' in t ? t.debit : t.credit;

CFA is not limited to if blocks — it also works for early return / throw, ternaries, && chains, and so on:

// these all work

function getString(arg: unknown): string {

return typeof arg === 'string' ? arg : '';

return typeof arg === 'string' && arg || '';

if (typeof arg !== 'string') return '';

return arg;

if (typeof arg !== 'string') throw new TypeError('arg is not string');

return arg;

}TS tries its best to narrow types in more complex situations than just a direct condition. For example, since TS 4.4 you can put the narrowing condition into a variable:

const x: string | number = '';

const isNumber = typeof x === 'number';

const y: number = isNumber ? x : 0;However, a bunch of operations that should, in theory, narrow the types, have no effect on TS:

const mixed = [1, 2, 'a'];

const nums: number[] = mixed.filter(x => typeof x === 'number');

const countries = ['de', 'us'] as const;

const str: string = 'de';

const country: 'de' | 'us' = countries.includes(str) ? str : 'de';

const nums2: number[] = mixed.every(x => typeof x === 'number') ? mixed : [];Which brings us to user-defined type guards.

Type guard functions

TS lets you mark a function as a type narrowing condition by making it a user-defined type guard — just put arg is SomeType into the return type:

function isDate(arg: {}): arg is Date {

return arg instanceof Date;

}However, as of TS 4.9, a function is never inferred to be a type guard based on its contents — you just get a normal (arg: Something) => boolean type. This lack of automatic guard inference is exactly why filter and every failed to narrow the array types. Adding an explicit type guard signature fixes it:

const mixed = [1, 2, 'a'];

const isNumber = (x: unknown): x is number => typeof x === 'number';

const nums: number[] = mixed.filter(isNumber);

const nums2: number[] = mixed.every(isNumber) ? mixed : [];Another weak point of TS guard functions is that they are not typesafe. The guard function might contain most absurd and outrageous checks, and TS will be OK with that:

function isNumber(x: unknown): x is number {

return true;

}

function isString(x: unknown): x is string {

return typeof x === 'boolean';

}

function isObject(x: unknown): x is object {

return Math.random() > 0.5;

}Switching over variable type

Regardless of the flavor, type guards let us safely do different things based on a runtime variable type — ideally, covering all the possible cases. For example, let's extract a DOM node from a parameter that can be either a selector or a DOM node:

function mount(where: Element | string | (() => Element)) {

if (typeof where === 'function') {

render(where());

} else if (where instanceof Element) {

render(where);

} else {

// by exclusion, "where" is a string selector here

document.querySelectorAll(where).forEach(render);

}

}This is very handy!

Downcast functions

Wouldn't it be nice if, instead of writing typechecks over and over, you just had a function that takes a wide-typed variable and magically returns a narrow type? Let's call these nice things "downcast functions" (Alexis King calls them "parsers" in the article I got the idea from — "Parse, don't validate", but parsing feels too strongly associated with de-serializing in JS, hence the name change). An example would be:

function toNumber(arg: unknown): number {???}Unlike user-defined type guards, this function is fully type-checked by TS. Using it is a pleasure:

const threads: number = number(process.env.THREADS);

const age: number = number(JSON.parse(data));The only remaining question is how to actually implement downcast functions. When the input type matches the output type, this is trivial:

function toNumber(arg: unknown): number {

if (typeof arg === 'number') return arg;

// ???

}However, when the input doesn't cleanly fit the output type, we must do something else. There are four viable options (and an extra funny one).

Convert

Certain input values can be converted to the output type in a logical way. For example, let's convert numeric strings to number:

function toNumber(arg: unknown, fallback: number): number {

if (typeof arg === 'number') return arg;

if (typeof arg === 'string') return Number(arg);

}If you manage to convert all the possible input values to output type — good for you! In most cases, though, some values don't have a sensible conversion — what's the number for an arbitrary object? So, we're back to the initial question of what to do with the remaining values.

Fallback

The simple way out is returning some "fallback" value. For number, a natural choice is NaN:

function toNumber(arg: unknown): number {

if (typeof arg === 'number') return arg;

return NaN;

}In some cases, a more useful default exists. When reading the "number of times the user viewed a banner" from localStorage, you might default to 0 for missing or invalid values. You can even accept a default in the argument:

function toNumber(arg: unknown, fallback: number): number {

if (typeof arg === 'number') return arg;

return fallback;

}Alternatively, you can fall back to null, letting the caller pass the default in ?? operator:

const offerViewed = toNumber(JSON.parse(json)) ?? 0;throw

Sometimes, there's no sane value to fall back to. True story: we have a REST to GraphQL proxy. GraphQL requests might return null or undefined for missing values, but, since our REST endpoint is obliged to send some value in a 200 response, we used to manually return 404 / 5xx responses for nullish values:

export const GET = apiHandler(async () => {

const { user } = await executeQuery(`

query UserId {

user {

id

}

}

`);

if (!user) {

return new Response('', { status: 404 });

}

return { id: user.id };

});It was quite inconvenient, since every call site has to worry about the case of missing values. Trust me, this gets out of hand real quick. It's much better to throw on unexpected values, let the caller ignore the case of invalid values altogether, and handle all the errors in one location (here, apiHandler). We greatly simplified our code with this simple non-null downcast:

function exists<T>(value: T | null | undefined): T {

if (T == null) throw new Error('MISSING');

return T;

}

const { user } = await executeQuery(`

query UserId {

user {

id

}

}

`);

return { id: exists(user).id };So, if unexpected values are an unrecoverable problem, and you have a single place to safely handle the errors, throwing is a perfectly good idea. Again, check out "Parse, don't validate" for a more in-depth explanation.

exit

As an alternative to throwing you can just stop the program with process.exit in node, or terminate browser tab with location.assign. Sounds pretty destructive, but sometimes it's a good way to proceed.

For CLI programs, it's convenient to exit when a required environment variable is missing. process.exit() returns never, which makes writing this helper a breeze:

function extractEnv(name: string): string {

const value = process.env[name];

if (value) return value;

console.error(`process.env.${name} is required`);

return process.exit(1);

}loop forever =)

As the ultimate way to avoid responsibility, you can spin off a while (true) loop on invalid value and call it a day. After this, the function will never return, so the question "what to return" makes no sense. You probably don't want this in real life, but theoretically this produces a correct program.

Wrapping up, there's a variety of cases where you need to do different things with a TS value depending on its type. Two main real-life scenarios where this happens:

- Reading data from untrusted external source: user input, localStorage, JSON strings,

process.env - Accepting various input types for API convenience:

mount('#app')ormount(mountNode)

as operator can push values into stricter types, but this causes bugs when your assumptions are broken. Instead, you need runtime checks on the variable to see if it fits your expectations.

TypeScript uses control-flow analysis to give extra guarantees about a variable (narrow its type) in code areas only accessible behind a runtime check:

function logDay(x: Date | null) {

if (!!x) console.log(x.getDay());

}You can wrap the code to check if the variable is of type T into a user-defined type guard:

function isNumber(x: unknown): x is number {

return typeof x === 'number';

}Unfortunately, TS will never infer a function as a type guard, and the code that checks the type is not validated.

A very neat (and type-safe!) alternative to type guards is a downcast function that takes a wide-typed argument and returns a narrow type, e.g. (x: unknown) => number. When the input doesn't match the output, you have four options:

- Convert the type, e.g.

if (typeof x === 'string') return Number(x). Not all types can be realistically converted to other types. - Use a fallback value — e.g. a

0. In particular,nullfallback leaves it up to the caller to decide how to proceed. throw, letting the caller choose between handling the error itself or ignoring it and leaving the handling to some higher-level wrapper.- stop the program with

process.exit()orlocation.assign

Here are all the options we discussed today, in a cute diagram: